Success is neither magical nor mysterious. Success is the natural consequence of consistently applying the basic fundamentals

This quote from American entrepreneur Jim Rohn was aimed at business people but struck a chord with me when thinking about fuelling for endurance athletes.

It fits so well because getting your fueling and hydration strategy right isn't the mysterious art form that some people believe it to be. As Rohn's quote suggests, the key is to consistently apply the ‘basic fundamentals’ in order to be successful...

So, what does that mean in practice?

The fundamentals of fueling

When you boil sports nutrition down to the fundamentals, there are 3 acute costs of taking part in endurance exercise:

- Calories burned (mainly in the form of carbohydrate)

- Fluid lost as sweat (water)

- Sodium lost in sweat

Of course, the wider topic of good nutritional practices for athletes is significantly more complex than the turnover of these 3 elements. But for me, the trio sit head and shoulders above the others in the hierarchy of importance during endurance exercise.

Replacing a reasonable proportion of these 3 elements, in relation to their rate and overall magnitude of loss, represents the ‘fundamentals’ that any decent fueling plan needs to address. We know this because even getting them ‘about right’ often results in successful outcomes in the real world.

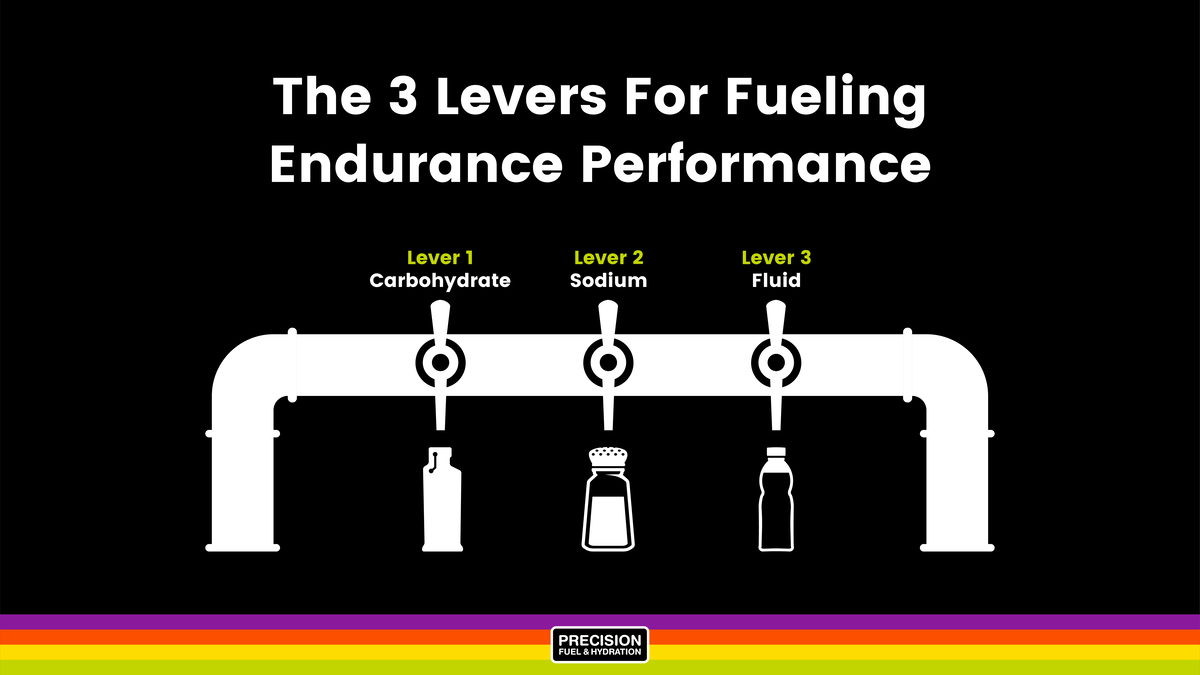

For this reason, Precision Fuel & Hydration often refer to the level of carbohydrate intake, the volume of fluid and level of sodium replacement as 'The 3 Key Levers’ of fueling for endurance athletes.

Pulling the 3 levers correctly

The way to learn how to ‘pull the levers’ correctly is to understand the ballpark levels of replacement that are usually needed for each one.

You can further refine these levels on the basis of your own deeper knowledge of your personal requirements.

And then (and this is the most important step), apply some structured trial and error to test out your estimates in the real world, and settle on amounts that work for you.

Before getting into the specifics of each lever, it's worth emphasising that the advice is based on optimising performance when going extremely hard in training or racing.

It doesn't necessarily apply in its entirety when undertaking easier training because requirements in all 3 areas will be reduced when rates of output are lower.

‘Lever 1’: Carbohydrates

How much to take in

Ingestion of carbohydrate has long been known to improve endurance performance, primarily during events lasting longer than 45 minutes (it's worth reading this paper by Asker Jeukendrup for an in-depth review of carbs and performance).

There's a lot of debate around the optimal dosage of carbohydrates because it can be so individualised, but there are credible guidelines on how much carb athletes need per hour.

The recommended amounts increase in line with the duration of activity, in recognition of the fact that stored ('endogenous') fuel is sufficient for shorter bouts of activity, but these stores become depleted over time.

So, we need to get more energy on board to avoid depletion and maintain performance levels for longer activities.

Not sure how much carb you need? Take the Quick Carb Calculator to get some fueling guidelines for your next event.

When individualising levels of carbohydrate intake for your own circumstances, the following rules of thumb are useful:

- If you're towards the smaller and lighter end of the body size spectrum, then you may need to dial the recommendations down slightly initially

- If you're of a bigger build, then you may find that tweaking them up a little makes sense

- If you're competing at a high overall performance level, you may benefit from being aggressive with these guidelines (due to a higher rate of energy output) if your stomach can handle it

What source of carbs is best?

In what exact format (i.e. gels, energy bars, carb drinks, chews) you get these carbs into your system is an area of furious debate, but I think it's a distraction from the fundamental issue of getting the correct amount of carbs dialled in as the first priority.

Of course, the format can matter (for example, in some cases Glucose/Fructose mixtures have been shown to be more effective when you’re aiming for very high levels of intake), but it’s very much a secondary issue to simply getting roughly the right amount of carbs in your mouth on an hourly basis.

Here are a few examples of products and their carb value:

| Product | Carbohydrates (in grams) |

|---|---|

| PF 30 Gel | 30 |

| PF 90 Gel | 90 |

| PF 300 Flow Gel (1 bottle/flask) | 300 |

| PF 30 Chew | 30 |

| Carb & Electrolyte Drink Mix (2 scoops in 500ml / 16oz) | 30 |

| Carb Only Drink Mix (2 scoops in 500ml / 16oz) | 30 |

| Banana | ~23 |

| 4 x Jelly Babies | 21 |

| Energy Chews | ~24 per serving |

| Picky Bar | 24 |

| Mixed nuts (100g) | 21 |

It’s wise to start with any source of simple carbohydrate-based fuel (i.e. without substantial fat, protein or fibre in the mix) that tastes good and you’ve had some success with in the past.

Keep this component consistent when you’re doing your trial and error testing and avoid introducing additional variables into the 'experiment' as they could skew your findings.

In my experience, plain energy chews, gels or bars with clearly marked carbohydrate contents on the packaging are the best way to go as they are often easily digestible.

How to refine your carb intake through trial and error

The best way to go about the trial and error process is to perform simulation training sessions where you perform the activity you're fuelling for as close to race intensity for a prolonged period of time (ideally close to race duration too).

Try using the following method:

- Measure your output with either wattage, pace/speed, heart rate and even a combination of these metrics using 3 Levers Nutrition Spreadsheet

- Record subjective assessments of how hard it felt (RPE)

- Record details of the weather conditions (or the temperature and humidity if training indoors), as well as any other useful pieces of information (e.g. time of day, whether you undertook the session fasted or after a decent meal)

- Record exactly what you ate (and drank), how many carbs you took in per hour, how you felt overall, and specifically whether you suffered any GI issues.

- Repeat a few times whilst trying to only significantly vary the amount of carbs you consume and keeping all the other factors as consistent as possible.

This approach will allow you to build up an initial picture of what different levels of carbohydrate intake are doing to your ability to perform (and to your stomach).

Persist with the testing and, alongside what you've learned during minor racing, you’ll really start to figure out what works for you and identify any emerging trends.

Whilst there are some inter-individual differences in the amount of carbs that are needed to sustain performance, there seems to be relatively less intra-individual variance.

What this means is that once you have your own carb intake dialled in, you can be reasonably confident that it won’t change too dramatically from day to day when duration and intensity are similar (assuming you've maintained stable fitness levels and you start the session well fuelled).

‘Lever 2’: Fluids

Optimal carb intake is reasonably stable once you dial it in, but fluid loss (via sweating) is significantly more volatile, both between and within individuals.

So, hydration requirements can be lot more variable too (in no small part due to the huge role that environmental conditions and clothing can have on sweat rates).

For these reasons, giving guidance on the ‘ballpark’ amounts of fluid intake to start some trial and error is more challenging than it is with carbohydrates.

How to work out how much fluid you need through trial and error

One sensible way to approach this issue is to start at the edges and to work inwards by beginning with the lowest amount of fluid intake needed...

-

For activities of less than ~60 minutes (and even up to 90 minutes in some cases), fluid intake of close to zero is definitely an option if an athlete starts well hydrated and has plenty of access to drinks to top up again afterwards.

This is certainly true in colder conditions when sweat rates are blunted because core body temperature is much easier to manage.

It remains a good idea to have fluids to hand (where practical) during most activities so that you can drink to the dictates of thirst but, unless it’s incredibly hot or humid, simply drinking to thirst is probably sufficient.

-

When you get into the zone of 2-3 hours (and in hotter and more humid conditions), fluid intake definitely starts to be required to maintain optimal output when you're going as hard as possible.

Without it, sweat losses can result in a decrease in blood volume that manifests in cardiovascular strain and a reduction in performance.

Once again, drinking ‘to thirst’ may be sufficient for quite a number of people as the accumulated sweat losses can usually be offset sufficiently by simply drinking when you feel like you need to.You’ll often finish races or sessions dehydrated in terms of percentage body weight loss but that’s arguably normal as long as you’re not also getting super thirsty or having to slow down prematurely (See this article for a detailed discussion of percentage body weight loss and performance).

It's true that a more structured approach to drinking might be beneficial for this kind of duration in certain situations (e.g. you’re a super heavy sweater, you're aiming to recover very quickly to train or compete again during the 24 hours following that session, or if you’re a novice and not great at listening to your body yet). In these cases, some experimentation starting around ~500ml (~16oz) per hour and adjusting up or downwards from there as necessary is sensible.

-

For much longer sessions and races (i.e. 3-4+ hours) in everything except the coldest conditions, I’ve always found it better to stick to an outlined hydration plan (albeit a flexible one), especially in the first half of the event when drinking to thirst can result in under consuming fluids and then dehydration creeping in later on.

Due to the huge variance in sweat rates and absorption rates in the gut, a ‘sensible’ level of fluid intake to aim for early in a longer session could be literally anywhere between 250ml (~8oz) an hour to somewhere close to 1.5 litres (~48oz) per hour at the very extremes.

Whilst that sounds like (and is!) a very wide range, it's fair to say that for a large majority of athletes something in the range of 500ml-1000ml (~16-32oz) per hour is a decent zone in which to start some experimentation.

Obviously start at the lower end of this band if your sweat rate is low and/or conditions are milder. And be more aggressive if you have a big sweat rate (see this article for details on how to measure your sweat rate) or if the conditions are very hot or humid.

Be very mindful that hyponatremia is a real risk if you significantly overdrink. This article is a useful resource to look at to understand the topic in more detail.

In my experience, it's rare to see athletes need to drink much more than 1 litre (~32oz) per hour for prolonged periods so I’d rarely advise experimenting above that level, and exercise caution if you do feel you need to go that high.

One thing that can’t be emphasised enough for long races and sessions is that developing the ability to fine tune your fluid intake based on feedback from your body is crucial.

Whilst having a flexible drinking plan and understanding your own requirements is a big part of the process, it's clear that the very best athletes become highly attuned to their own needs and manage intake very dynamically in longer endurance events.

This inevitably leads to the best outcomes when you become skilled at it and there's no real substitute for building up a large database of experience to get to this point.

The following signs and signals of possible over/under-hydration are useful to think about:

Signs of not drinking enough:

- Thirst/dry mouth

- Light headedness/dizziness

Signs of overdoing fluid intake:

- Feeling bloated or fluid ‘sloshing around’ in your stomach

- Loss of interest in drinking

- Needing to pee frequently

As with the process outlined for refining carb intake above, it's well worth following a similarly structured trial and error process for taking in fluids and measuring sweat rates in a variety of conditions to build up some personal ‘rules of thumb’ that work for you.

This article describes in detail how pro IRONMAN athlete Allan Hovda has been measuring his own data and is starting to reap the benefits.

‘Lever 3’: Sodium

As we’ve written about extensively in the past, the sodium content of sweat varies dramatically from person to person and coupled with variations in sweat rate this can lead to huge inter-individual differences in sodium loss during exercise.

How to work out how much sodium you need through trial and error

-

For shorter activities (under about 60-90 minutes in duration), it's highly unlikely that even the heaviest, saltiest sweaters need to worry about sodium replacement too much (in the context of a single session anyway).

Starting well hydrated and with electrolyte levels topped up makes sense of course, as does consuming sodium along with fluids in recovery, especially if you’re aiming to train or compete again soon after that activity finishes.

-

When you get to durations of 2-3 hours at a high intensity and in conditions that drive high sweat rates, sodium replacement can start to be important, especially for those with heavy losses.

Because you already have ‘stores’ of sodium in the body, only a proportion of replacement is necessary and that could be anywhere from close to zero for those whose sweat/sodium losses are very light, up to something in the 1000mg/hour range for those who experience very heavy losses. So, this is the kind of range to start experimenting in.

-

When stepping up to the really long stuff (3-4 hours plus) the differences in sodium loss really starts to tell and there's potentially quite a large divergence between people who still require very little exogenous sodium input to those whose intake levels need to be very high indeed.

As a rough guide I’d consider anything around 200-300mg sodium per hour to be quite low (but plausible for some people) during 3 hour plus activities in warm or hot conditions and this might increase to ~1500mg/hour or even a little more in athletes whose losses are extremely high or in longer events.

For context and as a heavy & salty sweater, I found I needed to consume close to 1200-1500mg sodium per hour on the bike to maintain performance and set up for a good run when racing IRONMAN in the heat.

That's based on me having both a high sweat rate (1.5-2 litre per hour) and very salty sweat (~1800mg sodium loss per litre).More recently, you can check out this blog to get an insight into my nutrition & hydration strategy for the 2019 ÖTILLÖ Swimrun World Champs.

To help you figure out where to start your own trial and error process with sodium intake, it’s useful to either get your sweat tested or to estimate the approximate magnitude of your sodium losses.

You can then start to infer whether you’re best to start off playing around in the 200-300mg/hour range, up closer to the 1500mg/hour range, or somewhere in between.

How does pacing influence your fueling / hydration strategy?

No decent exploration of hydration and nutrition intake for endurance athletes should gloss over the impact that pacing has on the equation.

That's because when you’re aiming to go very hard and sustain performance over a prolonged period of time, a poor pacing strategy can screw things up no matter what you eat or drink.

This is important in the trial and error process as going off too hard in sessions or races and fading can sometimes feel like it’s down to some kind of nutrition-related failure, when it's actually got more to do with overstepping your actual ability or fitness level.

It gets confusing because going too hard (especially in the heat) can lead to dramatically reduced blood flow to the gut (this is reduced significantly during exercise of any level, but especially if you push too hard) and can mean that you're unable to absorb calories and fluids at rates that you could normally tolerate.

The result is a bloated, uncomfortable stomach and it can become unclear whether this is the cause of a slow down or the other way around.

To that end, it's always worth employing a conservative pacing strategy (i.e. going off a little easy) when testing changes to a nutrition plan so that you're confident that you won’t skew the results with poor pacing.

This doesn’t mean you need to go super easy but it’s worth planning for a 'negative split approach' to be sure.

Summary

If Jim Rohn is right and that “success is the natural consequence of consistently applying the basic fundamentals”, then getting a handle on your own carbohydrate, fluid and sodium requirements should be a high priority as an endurance athlete.

Whilst this is not a particularly difficult process per se, it's one that requires trial, error and iteration to work out the ranges of each element that work for you at various durations, intensities and in environmental conditions.

There's a strong interplay between these 3 key factors that adds a potential layer of complexity to the process – if you get 1 or 2 of them way out of whack it can affect the absorption of the others.

But that's why it's important to try to find the ‘Goldilocks’ amount for each. Once you do that, you'll find that everything starts to ‘click’ and the benefits will be obvious in terms of stable energy and performance levels (and a settled stomach).

Having worked with a lot of athletes over the years and talked about the minutiae of sports nutrition, the 3 fundamental levels of carbohydrates, fluids and sodium don’t get the attention they deserve.

If you knuckle down and learn how to pull the levers effectively for yourself, it's a very straightforward way to start to make a positive impact on your performance.