A question often asked by my swimmer and non-swimmer friends alike is “do you even sweat when you swim?”. The short answer is “yes, you do”. Rather than leave the conversation there, it’s worth exploring how you sweat when you’re immersed in water and how you can manage your hydration strategies for pool and open water swimming…

Do you sweat when you swim?

The primary purpose of sweating is to regulate your body temperature, whether you’re on dry land or surrounded by a body of water.

Whenever we exercise, the body produces heat energy.

Some of this energy is stored and causes an increase in core body temperature, which is noticed by thermoreceptors around the body. Normal core body temperature ranges between 36 - 38°C, (96.8 - 100.4°F) which may increase to 38 - 40°C (100.4 - 104°F) during exercise. Once temperatures of around 39.5°C (103.1°F) are reached, we typically begin to experience fatigue.

Because sweating is the body’s main way of regulating our temperature, we sweat anytime our core body temperature reaches a critical threshold.

So, this is happening throughout any form of exercise, including swimming, because heat is produced as a by-product of the metabolic activity of contracting muscles.

That being said, the literature suggests that we may not sweat quite as much when swimming as we do on land…

Why don't swimmers sweat as much as land-based athletes?

Over the years, a number of studies have investigated sweat responses in swimmers and the exact conclusions vary, although they support the theory that swimmers do sweat but to a lesser extent than runners, cyclists and other landlubbers.

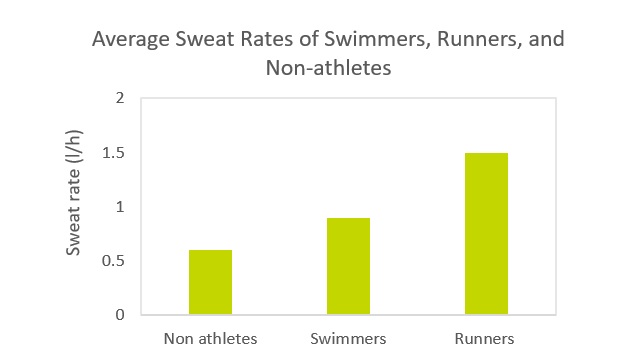

A study from 2010 compared the sweat rate of swimmers, runners and non-athletes after a 30-minute effort on a static bike. The results found the average sweat rate of non-athletes was lowest (0.6 L/h), followed by swimmers (0.9 L/h), with runners substantially higher (1.5 L/h).

This would fit with the theory that land-based athletes (who presumably stand to benefit most from the evaporation of sweat) develop more extensive adaptations to regular training, thus allowing them to sweat more freely in order to enhance cooling.

In contrast, swimmers’ bodies ‘learn’ to sweat to a lesser extent because it’s not as impactful to their body's thermoregulation in water. Interestingly, they do appear to sweat more than non-athletes whose daily routines don’t expose them to elevated core temperatures on a regular basis.

Other studies have found swimmers’ sweat rates to be even lower when training in the water, with averages of 0.315 L/h and 0.365 L/h.

In 2017, a large study with just shy of 500 athletes from various sports found the average sweat rate ranged between 0.5-2.5 L/h.

It's worth noting that many factors, such as the methods used to estimate sweat rates, the environmental conditions and exercise intensity, exert a significant amount of influence on sweat rates so it’s not surprising to see big ranges in this kind of data.

So, the trends seem to point to the idea that swimmers do sweat, just less than athletes doing equivalent land-based workouts.

For more on collecting sweat rate data, check out our blog How to measure your sweat rate to improve your hydration strategy and download the free Sweat Rate Data Calculator to start collecting your numbers:

Download the Sweat Rate Data Calculator.

Having recently hung up my racing goggles after many years as a competitive pool swimmer and invested in a wetsuit for open water swimming here in the UK, I can confirm that indoor and outdoor swimming are two very different beasts and need to be treated as such when considering sweat responses and hydration strategies…

Pool Swimming

At the risk of stating the obvious, we sweat more during intense exercise than we do during moderate intensity exercise because metabolic heat production is higher, so faster interval sessions and races are likely to result in higher levels of fluid loss than easier/steady-state workouts.

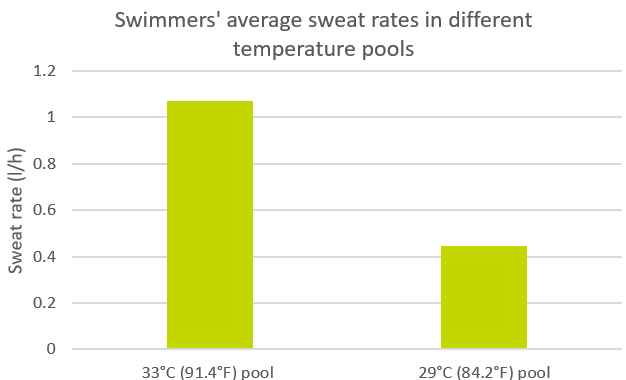

As might be reasonably expected, research has found hotter water temperatures result in significantly higher sweat rates than cooler temperatures. The average sweat rate recorded in a 33°C (91.4°F) pool trial was 1.07 L/h, which reduced to 0.445 L/h in a cooler 29°C (84.2°F) pool.

This happens because the hotter water temperature causes a bigger rise in body temperature, thus triggering our sweat response in order to try and keep the body cool (even if it’s not as effective as it would be on land).

Of course, if we lose a lot of fluid and don’t replace it, we risk becoming dehydrated and suffer a decline in performance. So, paying closer attention to hydration when training in warm water is a must.

As well as water temperature, the air temperature can have an effect on our sweat rates too. Anyone who has spent uncomfortable days on the pool deck at a swim meet will know what I’m talking about here!

The temperature and humidity around poolside is often high, causing both swimmers and spectators to sweat as soon as they walk through the doors and for as long as they remain in that environment.

Hydration strategies for pool swimming

1. Start hydrated

- Starting a pool-based training session or race optimally hydrated maximises blood volume and helps your cardiovascular system power your exercise.

- Higher blood volume also means your body can successfully dissipate more heat energy (due to increased blood flow to the skin), which allows us to maintain our performance for longer.

- Hydration becomes increasingly important in warmer water, where we will lose more fluid.

- Don't just drink lots of plain water before your training sessions or races as this can dilute the sodium in your blood.

- Consider adding sodium to your pre-race drinks as sodium helps maintain fluid balance and cognitive function.

- Try ‘Preloading’ with a strong electrolyte drink such as PH 1500 (which contains 3x the sodium of a typical sports drink) before your next big pool session as this helps to increase plasma volume without the need to consume huge amounts of fluid.

How to preload:

- Drink 1 x PH 1500 mixed with ~500ml of water the night before your event

- Drink 1 x PH 1500 mixed with ~500ml of water about 90 minutes before your event and aim to finish that drink about 45 minutes before you start swimming.

2. During training

- During training, water or a light electrolyte mixture will likely be sufficient to remain hydrated if sessions are 1 hour or less in duration.

- Keep a bottle on poolside and sip at it between sets if you feel you need to.

3. During races

- 1500 metres is the longest event in typical pool swimming competitions, which is still very short compared to many open water events.

- Focus on starting the race well hydrated and rehydrating afterwards.

- Do consider the temperature on poolside as this could increase your sweat rate and lead to dehydration. If the pool area is extremely hot and humid during a lengthy swim meet, consider using an electrolyte drink between races.

4. Rehydration and recovery

- Usually, drinking and eating normally after a typical pool-based training session will be enough to replace your lost fluids and electrolytes.

- But it may be worth considering supplementing sweat losses with an electrolyte drink if your sweat losses are high (i.e. if the pool or environment is hot or sessions are very long/twice a day).

- Many pool swimming competitions take place over 3-5 days, with races on multiple days. It’s important to stay on top of hydration levels throughout to maintain performance for every single race. Just drinking water alone (without added sodium) may not be sufficient if you’re spending all day on poolside several days in a row.

- So, try drinking a strong electrolyte drink (again PH 1500 is an ideal choice here) a few hours after your session to help speed up recovery and rehydration.

Open Water Swimming

In contrast to pool swimming, open water swimming is predominantly a long distance endurance sport. Events cover distances between 1.5km up to 10km and there’s a trend for many ultra-events to go even further.

The longer we exercise, the more time there is to sweat. So, pool swimming races may not create large fluid deficits, but open water races have the potential to dehydrate us pretty seriously.

As well as the event or distance we're swimming, we need to think about where we're swimming. As we've seen with pool swimming, water temperature plays a huge role in altering our sweat response and hydration status...

The impact of cold water

Do you often need to pee as soon as you get into cold water? This is a response from the body to regulate blood pressure.

Diuresis (increased or excessive urine production) frequently occurs when we swim for 2 reasons:

1. The cold temperature

When we're cold, the body prioritises blood flow to the working muscles and organs and constricts blood flow to the extremities in order to protect core body temperature. This causes an increase in blood pressure, which is noticed by receptors around the body.

The easiest way to reduce this pressure is by dumping some fluid. The kidneys help us to achieve this by filtering the blood, removing water, and producing extra urine that we then excrete.

2. Hydrostatic pressure

When we're submerged in water, some blood shifts from the feet and legs up towards the chest. This also enhances the increase in blood pressure, so again the body expels fluid through the urine.

These mechanisms help maintain our blood pressure, but the loss of fluid could cause us to become dehydrated over a long period of time.

Do wetsuits affect sweat rate?

Wetsuits are designed to keep us warm by retaining body heat. This is all well and good, but the increased body heat from swimming and the insulation from the wetsuit means we can’t offload this heat so easily, which could cause an increase in sweating (particularly in warmer water).

In fact, you can buy various ‘slimming outfits’ and ‘sauna suits’ made out of neoprene (the same material most wetsuits are made from) as they cause you to lose more weight through sweating (although it's not something we'd recommend!).

So, if you’re swimming in a wetsuit in warm water, you may need to pay closer attention to your hydration strategy.

To emphasise this point, we spoke to pro triathlete Sarah Crowley to find out how she approached the swim leg of IRONMAN Cairns, where the water temperatures are notoriously warm and present athletes with a difficult decision when choosing whether to wear a wetsuit or not…

The swim at IM Cairns is unique. The temperature on race day is 27°c and under normal circumstances this would be a non-wetsuit swim for both age group athletes (above 26°c) and certainly pros (above 21.9°c).

However, the waters off Cairns carry the risk of the highly toxic Irukandji or “Box” Jellyfish. Although it was not stinger season in Cairns, there was still the risk of a jellyfish sting. The officials decided to make the race "wetsuit optional" at 27 degrees, with a warning that this could be extremely hot and dangerous from a heat stroke perspective.

We had prepared for this scenario by wearing our wetsuits in the heated pool for a few weeks leading into the race and mitigated our risk on race day by pre-hydrating with extra electrolytes.

I personally shoved ice down my wetsuit one minute before the start and also pulled at the front of my wetsuit at each buoy to allow water in for cooling.

Professional triathlete Sarah Crowley, who has twice finished on the podium at the IRONMAN World Championships.

Hydration Strategies for Open Water swimming

Start hydrated

- The same basic advice for starting hydrated when pool swimming applies to open water swimming...

- First and foremost, it’s important to start a race or session well hydrated to make sure you can perform at your best.

- Try preloading:

- Drink 1 x PH 1500 mixed with ~500ml of water the night before your event

- Drink 1 x PH 1500 mixed with ~500ml of water about 90 minutes before your event and aim to finish that drink about 45 minutes before you start swimming.

Shorter distances (5km and below)

- In open water, there's often an opportunity to consume food and drink during the race, known as a ‘feed’. Floating or stationary feeding stations are typically placed throughout race routes or sometimes provided from support boats or kayaks.

- Unlike other sports, swimmers must substantially reduce velocity or come to a stop in order to complete a feed.

- Rolling onto your back and slowing down or completely stopping could affect your swimming rhythm.

- The position of a feeding pontoon often causes swimmers to deviate from the race course slightly, adding extra distance and seconds onto their overall finish time.

- The time taken for the feed would usually be deemed to offset any small potential benefits gained from fluid / carbohydrate intake in a race of 5km or shorter.

- So, swimmers taking part in events up to 5km should normally focus on pre-race nutrition and use strategies to optimise carbohydrate availability and hydration status before the race (i.e. carb-loading and preloading).

Longer distances (10km+)

- Swimmers should seek to utilise feeding stations in these races.

- The longer duration means that the benefits of taking in carbohydrates, fluids and electrolytes almost always outweigh the small time-losses incurred when pausing to get the feeds in.

- Carbohydrate intake is the priority in cooler water when sweat loss is less of an issue.

- In hotter temperatures, it may be that fluid and electrolyte losses become more problematic and therefore warrant more emphasis in these conditions.

- Feeding and hydrating during long duration swims is extremely individual, so swimmers should carry out some trial and error with different levels of fluid, electrolyte and carbohydrate intake in training to find out what works for them in different conditions.

- Feeding strategies should be practiced during training to make sure they’re as efficient as possible in the race.

During my solo Channel Swim I had a feed every hour, but you obviously have to stay in the sea so it's quite difficult. I had smoothies with oats, banana and soya milk and other than that I played it by ear depending on how I felt.

When training we would do one-hour loops and come back to the shore, and I would have the same smoothies. It didn't exactly replicate the Channel Swim, but I did get used to feeding every hour.

At the start of the swim, the feeds only took about a minute, but by the end I was taking longer because I was getting tired.

When you get cold it's hard to chew solid things, and I was planning to have a lot more solid foods but it just took too long to eat.

Another problem is that you don't want to stop for very long because you end up getting colder while you're not swimming, so the smoothies worked well.

Ex-national pool swimmer Naomi Vides completed a solo channel swim in 2017 and was a member of 2 successful English Channel relay teams.

The key takeaways

So, despite being immersed in water most of the time, swimmers definitely do sweat, albeit to a lesser extent than most land-dwelling athletes.

Pool Swimmers

Pool swimmers primarily need to be mindful of the effect that warmer water and high air temperatures can have on sweat rates during longer training sessions and over multiple days at swim meets.

This chronic heat stress can place more emphasis on good hydration practices and electrolyte intake when out of the water, but pool-based races are almost always too short to make in-race hydration or fuelling an issue.

Open Water Swimmers

For open water swimmers, the need to start races well fuelled and hydrated is critical because eating and drinking during events is often quite disruptive to performance.

For this reason, avoiding or minimising feeds in shorter open water events is recommended.

However, as races get longer (approaching 10km and beyond), feeding mid-race becomes essential to maintain performance.

So, practice different strategies in training to iterate your plan and learn what strategies work best for you as an individual.

If you have any questions regarding your hydration strategy, please don’t hesitate to contact our team of customer service specialists who will be more than happy to help refine your plan - email us at hello@precisionhydration.com or book a free one-to-one video call.