There's a common misconception among athletes and the general public that you're optimally hydrated if your urine is a clear colour. The colour of your urine can help you understand how your hydration status fluctuates on a daily basis, but drinking until your pee is clear is not the route to optimal health or performance...

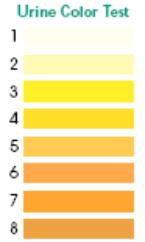

Urine Colour Chart - What colour is your urine?

Every time I visit the locker room of a pro sports team I make sure I visit the restrooms.

Often this is genuinely just answering the call of nature, but even if I don’t really need to pee I will usually make my excuses to go and take a quick look out of professional interest.

Now, I know this all sounds a bit weird, but hear me out. What I tend to go looking for is an ‘Armstrong Chart’ pasted up on the wall above the facilities.

Armstrong Charts look a bit like a paint colour swatch you’d find in any DIY store. They show a range of 8 hues gradually transitioning from off-white, through various shades of yellow, to finish on a nasty greenish looking brown.

These charts can be found in nearly all bathrooms in elite sports facilities. I’ve spotted them in the toilets of just about every single NBA, NFL, MLB, NHL, NCAA College, Premier League soccer and rugby team that I’ve visited over the last 10 years.

How valid is the urine colour chart?

The Armstrong charts take their name from Dr. Lawrence E Armstrong, who ‘invented’ the concept of taking a close interest in your urine output and he’s most famous for attempting to validate his chart’s accuracy for predicting hydration status in two papers published in the International Journal of Sport.

In the team sports environment, these posters are often appended with provocative statements from team management. If you’re not in the 1-3 zone, you’re letting yourself down and you’re letting your teammates down. Heaven forbid - you find yourself in the 7-8 (dark) area; you’re definitely classified as ‘dehydrated’, you're a sub-standard human being, and you need to DRINK MORE!

I believe the charts - and the widespread and vigorous promotion of the research that helped to validate them - are the main reason sports people are often obsessed with the colour of their pee (and what that means for their hydration status).

But, recent research has cast some doubt over exactly how valid using urine markers alone to monitor your hydration status might much of the time.

I asked the lead author of the recent British Medical Journal paper ‘Dehydration is how you define it: comparison of 318 blood and urine athlete spot checks’, Dr Tamara Hew-Butler (who we collaborated with on some research into the cause of hyponatremia in sports last year) to give me a quick summary of what she thought the main take home points from her research were for athletes…

“Equating dehydration with urine that is "less than clear" (i.e. yellow to brown) has become popular among sports coaches and trainers, because testing urine is cheap and easy.

Plus, the colour chart is very cool and makes everyone feel as if they’re an expert.

However, the science behind these urine colour charts mainly came from looking at the accuracy between urine variables (i.e. colour versus urine specific gravity versus urine osmolality) with changes in body weight (also cheap and easy to measure)."

Does dark urine mean you're dehydrated?

Dr Hew-Butler went on to say, "Very few studies looked at urine versus blood variables. Studies (like ours) that looked at blood markers of cellular hydration (which is what doctors look at when assessing hydration status in patients) found NO relationship between cellular dehydration (blood sodium above 145mmol/L or "hypernatremia") and urine concentration.

Our body defends against cellular dehydration by changing the amount of water retained or lost by the body. So, dark coloured urine just means that our body is retaining water to protect cell size.

It’s only when we drink fluids above what our body needs that we produce clear and copious amounts of urine. Thus, the more we drink (above what we need), the more we pee.”

So, what Dr Hew-Butler is essentially saying is that, whilst there is definitely a relationship between how much we drink and the colour of our pee, that doesn’t necessarily always correlate with our actual hydration status at a blood and cellular level (where it really matters).

I find this extremely interesting because, while it holds true for most athletes in most circumstances, I’ve increasingly felt that the apparent obsession with ‘peeing clear’ is not necessarily always a completely helpful a message to be promoting to athletes. I’ve seen it drive some pretty questionable behaviours in my interactions with sports people (from elite to amateur) over the years, myself included! I’d go so far as to say that it can actually be counterproductive in some circumstances.

Because the “clear pee = well hydrated” message has been pushed so hard, I’ve witnessed highly motivated athletes over-drinking routinely in a bid to always pass large quantities of transparent urine, in the firm belief that anything less than that is somehow sub-optimal. I was definitely guilty of this myself in the past when in full-time training (and before I got into the hydration game).

It’s also partly why so many athletes consciously over-drink immediately before competing. This can lead to problems associated with hyponatremia (the dilution of the body’s sodium levels), which can ruin your event and can even be life-threatening in the extreme.

In one pretty outrageous example, I’ve chatted with a high profile NFL Starting Wide Receiver who is adamant that if he doesn’t drink so much water that he “pees his pants on the sideline” at least twice before the start of each game, he’s sure he’s not ‘hydrated’ enough to perform at his best.

In the organisational context, I’ve seen pressure put on athletes by coaches or sports medicine staff. Sometimes they'll actively testing ‘urine specific gravity’ or ‘urine osmolality’ on a daily basis, with punishments for athletes who present with dark coloured urine.

This can often result in some significant over-drinking going on before pee tests and even the watering down of urine samples in the changing rooms. I kid you not. Pro tip: if you’re going to do this, use the hot tap otherwise the Pee Test Officer may become suspicious if you hand over a cup of stone cold pee.

Placing such specific and heavy emphasis on urine colour as THE ONLY critical hydration metric incentivises athletes who focus on over-drinking, rather than just drinking appropriately.

It also fails to adequately promote the message that, although being chronically dehydrated is definitely bad, so too is chronically over-drinking (especially plain water) and forcing your body to urinate more frequently than is necessary just to check that you have clear pee the whole time.

There’s a tendency in sports medicine (and - to be fair - in most walks of life) to focus on measuring and improving metrics that can be easily measured/quantified and this is what seems to have happened in the quest to quantify hydration status.

The relationship between urine colour and hydration status

Hydration status is something that most coaches and athletes are, quite correctly, interested in getting right. The issue is that, whilst urine colour can definitely be somewhat indicative of hydration status, there’s definitely not a simple and linear relationship between actual hydration status and the colour of your pee. Frequently producing very small amounts of dark urine can be a sign of actual dehydration, but it’s not necessarily always the case.

With those points in mind, numerous other factors can affect the colour of your pee (as this excellent article points out) and these include…

- Drinking alcohol

- Drinking a lot of tea, coffee or other mildly diuretic drinks

- Swimming in cold water (due to cold diuresis and/or immersion diuresis)

- Drinking a large amount of plain water in a very short space of time

- Nerves

- Certain medications

So, boiling a complex topic down to an overly simplistic statement - "your pee should be 1-3 on this chart" or "you’re not hydrated enough!" is appropriate for many - but misses many important nuances and creates the potential for the key message to be misinterpreted and drive behaviours that aren’t actually helpful. i.e. to promote over-drinking.

It makes me think of the famous quote that is often attributed to Einstein; ‘Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.’

Urine colour and dehydration - Practical applications

Despite the weaknesses of the ‘Armstrong Chart approach’, I do still think that keeping an eye on what colour your pee is from time to time can be a useful tool in helping to manage your hydration status, as long as it’s not the only tool you use.

If you’re regularly nearer to the ‘8’ end of the scale than the ‘1’, then it might be worth experimenting with taking in a little more water or sports drinks, especially around times when you’re working hard and sweating a lot. See how that makes you feel and whether it’s of benefit.

Conversely, if you’re always seeing 1-2 coloured pee, then maybe you could think about dialling back your fluid intake a touch to see if you’re over-doing it a bit.

Again, how you feel overall after making these adjustments will give you the best idea of whether you’re better or worse off as a result, and that is of course what actually matters most of all.

But I do think it’s important that we start to move away from the overly simplistic idea that if your pee is clear you’re definitely hydrated, and if it’s not, you’re definitely not.

This is not the case all of the time and drinking and drinking until your wee is clear is not the route to optimal health or performance. As a result I think I’d be happy to see some of these pee charts coming down off the walls in the near future. Or for the messaging to be changed to something a bit more nuanced.

It’s generally a good idea to provide prompts to help athletes self-monitor and understand their bodies a little better. But it’s important that those prompts ‘nudge’ the development of genuinely helpful behaviours and, to a degree, it feels like we may have strayed a little too far in one direction in this case.