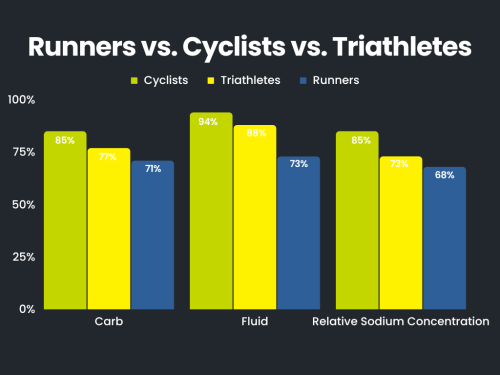

After crunching the aggregate data from hundreds of Athlete Case Studies, we discovered that runners were hitting the Fuel & Hydration Planner's recommended guidelines for carbohydrate, sodium and fluid less often than cyclists and triathletes.

As part of a round-table discussion, The Morning Shakeout host and running coach, Mario Fraioli, joined Precision Fuel & Hydration Sports Scientists, Andy Blow and Emily Arrell, to compare the training and race nutrition habits of endurance athletes...

Are runners worse at fueling?

Mario Fraioli: During more than 20 years as an athlete and coach primarily involved with distance running, it struck me that runners seem less adept at fueling and hydrating than cyclists and triathletes. It's interesting that you've observed that in your Athlete Case Study data...

Emily Arrell: We've done over 300 Athlete Case Study analyses of race fueling strategies of runners, cyclists and triathletes. We have a ‘traffic light system’ that rates how well their intake matches the general recommendations for carbohydrate, sodium and fluid.

So, the intake is rated ‘green’ if it falls within the general recommendations, ‘amber’ if they're just outside the recommendations, and ‘red’ if they’re over or under-fueling for the event’s duration and intensity.

We've seen a higher percentage of cyclists hitting ‘green’ for carb, sodium and fluid intake, with runners consistently ranking at the bottom.

Mario: Why do you guys think that is? Is it just easier to get more in on the bike?

Andy Blow: I know when I get ready for my long-ish run on a weekend, I debate whether it’s long enough to justify the hassle of finding my running belt, because I would prefer to just get out there!

In contrast, it’s easier to go out on the bike with two full water bottles on your frame, pockets that are designed for carrying bars and gels, and you're also not really breathing as hard all of the time. There's often stretches where you can virtually 'free wheel', so getting the fuel and fluids in is easier.

Comparing fueling habits

Mario: One thing I've observed and am certainly guilty of myself in the past is not eating before I run because I'm worried that it's going to bother my stomach. I’ve noticed a recent shift in that attitude in runners though and when I do make the effort to get some carb on board, I perform and recover better…

Andy: With runners, not fueling adequately is more likely to impact recovery than it is performance. It'll impact performance in the long run and it might impact performance in your second run if you're doing two sessions a day.

I think part of the problem is that lots of runner's sessions could be between 30-60 minutes in total duration and therefore you can complete it on an empty stomach.

Whereas cyclists and triathletes are often going out for two-hour plus sessions where you can't realistically complete it without eating or drinking, unless you want to feel pretty lousy at the end.

My personal view is that runners get conditioned early on to work around underfueling because it's not a big problem day-to-day. Where it bites you is when you start doing the two-hour sessions or the really long races, because habitually you're used to skimping rather than maximising your intake.

Mario: I think that's an important point. In my experience, cyclists and triathletes have a plan going into these sessions. For example, “I'm going to fuel every 20 minutes”, whereas runners say “maybe I'll have a bottle close by if it’s hot”. So, I think there's a cultural aspect where fueling and hydration isn’t part of the conversation for a lot of runners, while it's ‘the fourth discipline’ of triathlon.

Andy: When runners do start to experiment using a carbohydrate drink during a track session involving 30 minutes of really powerful effort, they find that they can push out the final reps a lot faster and recover faster off the back of it. That's where that light bulb goes on.

But I still think it's the same as it ever was in a lot of coaching environments where people are doing those sessions. It's just not, to your point, culturally accepted that it's a necessary thing to do.

It could almost be seen as a bit of a weak thing to be doing, as opposed to being something that's beneficial.

Make a plan

Mario: I've seen a lot of runners do fasted long runs or maybe not take much during training runs, and that ends up being what they do during race day. They just don't go in with a plan.

They think, “OK, there's an station at 10km and 20km, so I'll grab a gel then, and I know there's water every mile", or "I’ll drink when I'm thirsty". And for some folks, that might work out, but a lot end up crashing and burning in the last few miles of the race.

So, how important is it to start putting a plan in place during training?

Emily: Really important. With a plan, you're able to fully see what your gut can tolerate. So, use your sessions to see the level of carb intake that you’re happy with, build up by training your gut and you’ll be able to hit higher numbers to perform better in your training.

Mario: Switching gears, one interesting stat that you guys picked up in your case studies was between marathoners and ultrarunners. It was a fairly small sample size but comparatively, ultrarunners did a much better job of hitting their recommendations for carb, sodium and fluid intake. Is that because of the differences in duration and intensity of the events?

Emily: I think the intensity impacts the type of fuel people take on, so ultrarunners will have more bars or real foods compared to gels.

Mainly, I think it’s because ultrarunners are going in with more of a plan. They're carrying more of their race nutrition with them and are less reliant on the aid stations - they know that they can get enough in without having to be too reliant on what’s on course.

Andy: I'd second that. It doesn't take too many ultras to realise that you absolutely have to fuel and hydrate effectively. Whereas we know that the marathon is on that borderline where a lot of people in the past would run it with the minimum that they could get away with.

What we’re seeing increasingly with the marathon runners is that more people are starting to adopt the idea of fueling.

I think one of the most telling examples of this would be with the Nike Breaking 2 Project. They were looking at how to break the two-hour marathon from every conceivable angle, both technological and physiological, and they put a very rigorous and pre-planned fueling strategy in place for those races. The guys on the bikes were making sure that the runners got access to high carbohydrate drinks when they needed them.

Those guys had every bit of sports science thrown at them, and they decided it was worth the ‘hassle’ to fuel.

Cultural shifts

Mario: To that point, I was questioning what some of my coached athletes were doing fueling-wise. I have an athlete who wouldn’t have any gut issues and could run a relatively even marathon split, but they’re only taking one gel an hour, so maybe 25-30g of carbs, and I’m trying to explain to them that they’re leaving time on the table.

If we could increase that intake over time, I think they could perform at an even higher level. And they understand that, in principle, but there’s a fear of their stomach not tolerating it and a hesitation to change anything from a fueling standpoint.

Andy: Coaches are often rightly focused on getting their athletes fit and getting them to the start line in the best possible shape. The focus is on a pacing plan and a tactical approach to the race, but they don't necessarily always feel qualified to really talk in detail about the nutrition side. Then what happens is that people fall back on their own experiences.

We're still in an era now where we've only really been talking about high carbohydrate fueling for marathon runners for a handful of years. So, most people's prior experience falls back to that era of taking as little as possible. I think all of those things create the same downward pressure, especially if they’re new or inexperienced, they're relying on their coach as pretty much the sole source of good information.

Mario: In recent years, the easy explanation for the continued improvements in marathon performances at the very top is, “well, of course it’s the shoes”. Which is true, but there’s been a lot more attention paid at the top of the sport to how these athletes are fueling in training and during the race itself.

And it’s clear that if you’re going to be running at a high-octane level you need to be putting high-octane fuel into the tank. My suspicion is that over the next 10 years in marathon running, the conversation is going to shift and fueling is going to be more culturally accepted.

As you were saying earlier Andy, amongst a lot of the older school runners, it’s become a point of pride to say, “Oh I didn’t take anything". I think that’s going to be a story of the past not too long from now.

Andy: My old boss was a very good triathlete back in the 1980s and a mid-2:20s marathon runner. He told me that every marathon he did, he followed the example of Ron Hill and was convinced it was all about ‘toughing it out’ by not taking a drink until you were really parched and not taking any calories in.

Every single marathon he ran, he fell apart or slowed down significantly in the last few miles. It was an accepted part of the game. That was just what happened and his reasons was always, “I haven't done enough miles” or “I shouldn’t have gone out so hard.” Nutrition was never part of the conversation for him.

I was curious to ask you, Mario, about the cultural side of running and exercising for weight loss, and whether that creates another pressure to not eat during runs?

Mario: I’ve definitely come across examples where runners have viewed it as a wasted opportunity to burn calories. One thing I’ve heard too is, “I don’t want my sodium intake to be so high because I’ve heard that it’s not healthy to have a lot of sodium in your diet.”

Andy: I think it's all part of the same mindset. Basically, when you’re exercising, we're advocating for people to eat and drink the things that we're being told on a daily basis not to consume. And the simple answer for that is that when your body's either burning energy or sweating at a high rate, like it is when you're running, your turnover of energy, fluid and sodium is so much higher.

If you're a heavy sweater and you're running on a very hot day, you can sweat out an absolute ton of fluid and sodium. So, putting it back in at that point when you’re really needing it, is the best possible thing you can do. It'll make you feel way better. If you eat energy gels and drink sports drinks when you’re just sitting on the couch every day, you're gonna give yourself serious metabolic problems.

Mario: Yeah, and I think that’s another of those cultural shifts we've talked about that we’re going to see happening in running, whereas it’s been part of the culture in triathlon and cycling for a lot longer.

Andy: On that note, it would be great to see more running apparel companies looking at designing clothing that easily accommodates gels and bottles and drinks. I've got some brilliant shorts with pockets on the legs and around the waistband, so you can carry a flask and gels easily. But you can’t carry anything in the traditional marathon running outfit of a singlet and split shorts.

Mario: Funny you mention that. My first marathon was in 2007 and my kit was a singlet and a pair of split shorts with no pockets at all. I wasn’t very good at fueling at the time but I took gels - only two, admittedly - and my Mom sewed pockets into my running shorts. Fast forward 16 years, there are a lot more apparel options with built-in pockets that make carrying fuel much more accessible.

Mario: Finally, based on your case studies, what are some of the easiest adjustments that runners can make to improve their fueling and hydration strategy?

Emily: As we've discussed throughout this conversation, start putting a plan together. Athletes can keep a record of how much they're eating and drinking during sessions.

And then they can look at what they can happily tolerate. So, when they look to increase that through gut training, they can be more confident that they can take on a certain target of carb per hour during races.

Mario: I think that’s a good point and something I’ve encouraged my athletes to do. In the past, they track all of their mile splits and distances, but fueling and hydration isn’t something that they’ve ever tracked in training. When they start doing that, we can say with certainty, “you took in this much carb, sodium and fluid”. And we can then correlate that with performance and see if they can adjust anything. The simple act of tracking it allows you to make refinements.

Andy: Wouldn't it be brilliant if apps like Strava asked you, “what did you hydrate with?”. It would be a little bit subjective, but even just an appreciation for the average pace that you managed to maintain in sessions that you fueled compared to when you didn't would be great. Over time you'd build up a really powerful picture.