“The competitors who had extremely low blood sugars presented a picture of shock!” That was how scientists described athletes crossing the finish line at the 1924 Boston Marathon.

A year later, the same group of scientists observed that athletes who ate sweets and gummies before and during the race finished in a much better condition and with higher blood sugar levels, leading them to conclude:

"The adequate ingestion of carbohydrate before and during any prolonged and vigorous muscular effort might be of considerable benefit in preventing low blood sugar and the accompanying symptoms of exhaustion".

This was the earliest recognition of the importance of using carbohydrates to fuel endurance performance and avoid hitting the infamous ‘wall’.

The scientific literature has come a long way since then. We take a look at what the latest research says about how to fuel your marathon, so you can avoid presenting a ‘picture of shock’ when you reach the finish line…

How to fuel your marathon

An effective nutrition strategy should focus on replacing a decent proportion of the three acute costs of running a marathon:

- Calories (mainly in the form of carbohydrates)

- Fluid (lost through sweat)

- Sodium (lost in your sweat)

Of course, the wider nutritional considerations of running 42.2km are a lot more complex than this, but carbs, sodium and fluid should form the fundamental basis of your strategy.

We call these ‘The Three Levers’. How you ‘pull’ those levers on race day will be impacted by your race intensity, duration and the weather conditions.

The guidelines for optimal carb and fluid intake below are based on the current scientific literature and our own experiences of working with marathon runners. They provide a framework for you to dial in your strategy through trial and error in training…

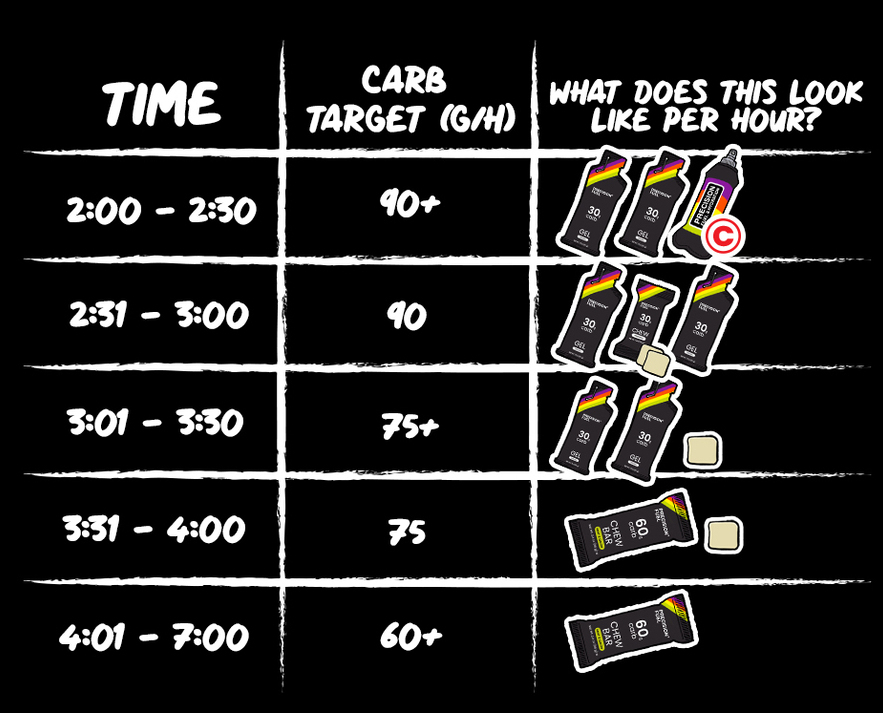

| Target time (h:min) |

Target carb (g/h) |

Target fluid (ml/h) |

|---|---|---|

| <2:30 | 90 - 120 g/h | 300 - 600 ml/h |

| 2:31 - 3:00 | 75 - 90 g/h | 300 - 600 ml/h |

| 3:01 - 3:30 | 60 - 90 g/h | 300 - 600 ml/h |

| 3:31 - 4:00 | 60 - 75 g/h | 300 - 600 ml/h |

| 4:01 + | ~60 g/h | 300 - 600 ml/h |

(General recommendations for temperate conditions, ~8-15℃ / ~46°-59°F)

If you’re thinking, ‘there’s no way I can eat and drink that much during a marathon’, don’t worry, you’re not alone. But just as you can train your legs to adapt to race pace over time, you can train your gut to handle more carbs without distress too...

Lever 1: Carbohydrates - Train your gut

Glycogen is how our body stores carbohydrates, and on average we have around 500g split between the liver and the muscles. The absolute quantity of stored glycogen will vary based on body size, fitness level, eating habits and other factors. But these stores are usually enough to fuel ~90-120 minutes of marathon effort, meaning you’ll still need to top up during your event.

Elite marathoners regularly consume 90-120g of carbs per hour during races, but this doesn’t happen overnight. For these athletes to run to their potential on race day, training their gut to tolerate more carbs is just as important as training their aerobic capacity.

If you attempt to emulate elite runners without gut training, you might run into some common issues:

- Suffer GI distress due to trying to consume more carbs than you can tolerate

- Underfuel because you’re not used to taking in enough carbs while running

- Hit the ‘wall’ because your body isn’t absorbing fuel or fluid efficiently

How to train your gut:

- Use a structured gut training protocol

- Aim to start 8-10 weeks before race day. This can help increase absorption rates and tolerance

- Start small. If one gel per hour feels tough now, start there and work up gradually

- Mimic race conditions. Practice fueling at race pace to get your gut used to it

- Mix it up. Try gels, chews, drinks - whatever format of fuel works best for you

- Listen to your body. If something causes discomfort, adjust your approach rather than forcing it. Any increase from your baseline is a win

Your progression won’t always be linear like the image below, but the gut is highly adaptable, and incremental increases over time can lead to significant improvements.

Lever 2: Fluid - Measure your sweat rate

Whilst your target carb numbers will be relatively fixed once you’ve dialled them in, how much fluid you drink can be variable from one race to the next. This is because your sweat rate (i.e. how much fluid you sweat out) is influenced by factors such as the ambient temperature and humidity, how hard you’re working, your clothing choices, genetics and heat acclimation status.

Given that most marathons take place in temperate conditions (~8-15℃ / ~46°-59°F)), dehydration caused by an excessively high sweat rate isn’t usually a major concern for most runners. That said, mis-managing hydration - whether drinking too little or too much - can still negatively impact your race.

Dehydration occurs when fluid loss (primarily through sweating) drastically exceeds how much fluid you drink, leading to:

- Reduced total blood volume and stroke volume, which makes running feel harder

- Increased core temperature and heart rate, resulting in fatigue

- Gastrointestinal (GI) distress as blood is redirected away from the gut

The effects of dehydration on endurance performance are well-documented, though they vary between individuals. One common benchmark is that body mass losses greater than 2% are associated with impaired endurance performance. As a result, hydration guidelines generally focus on avoiding this threshold as a minimum target. And avoid trying to replace 100% of your losses as this isn’t necessary. In fact, excessive fluid intake can result in bloating or a nasty condition known as hyponatremia (low blood sodium).

So, it’s worth experimenting in training with your own fluid intake. As a ballpark figure, drinking ~300-600ml (~10-20oz) of fluid per hour would be a suitable target in ‘normal’ marathon conditions, especially if you get to the start line well hydrated.

To dial in your own hydration strategy, measure your sweat rate in similar conditions to those you’re likely to face on race day…

Lever 3: Sodium - Are you ‘salty’?

The other factor to consider when it comes to hydration is your sweat sodium concentration, which refers to how much sodium you lose in your sweat. You do lose other electrolytes like magnesium, potassium and calcium in your sweat, but in much smaller amounts.

The amount of sodium you lose is generally a lot more stable than your sweat rate as it’s largely genetically determined, but it can vary enormously from athlete to athlete. After conducting thousands of Sweat Tests, we’ve seen huge variance, with some losing as little as 200 milligrams of sodium per litre (32oz) of sweat and ‘saltier’ sweaters losing more than 2,000mg per litre! Our data suggests the average athlete loses around 991mg/L and this tallies with other large scale studies.

So, what does this mean for how you pull the sodium ‘lever’?

It’s best to think of your sodium numbers in terms of the relative sodium concentration of your drinks. So, focus on milligrams of sodium per litre of fluid, rather than setting target amounts of sodium per hour. That’s because taking in too much sodium with insufficient fluid is a recipe for GI distress and excessive thirst, and also because sodium needs tend to increase in relation to total fluid intake as well.

Your sweat sodium concentration is unique to you, so individualisation is key.

- A low concentration of sodium to take in is ~500mg/L (i.e. for athletes with lower sweat rates and sodium losses, and in cooler weather)

- If you’re unsure where to start, ~1000mg/L is a sensible place to begin some trial and error during training

- A concentrations of ~1500mg/L tend to be as high as most athletes need to go. (i.e. for heavy and saltier sweaters, or those running longer races in very hot conditions).

The easiest and most accurate way to understand how much sodium you lose in your sweat, and therefore the sodium numbers you should be aiming to hit during your marathon, is to get a Sweat Test.

But if you don’t have access to one, you can still make a reasonable estimate by looking out for the six signs that you’re a salty sweater. Interestingly, research shows a strong correlation between an athlete’s perception of their sodium loss and their actual measured sweat sodium concentration.

Right, so you’ve got your numbers. It’s now time to work out how you’re going to hit them during your marathon…

What will you eat and drink?

There are two major considerations here:

- Which format of fuel will you use?. We’ve weighed up the pros and cons of gels, chews, drink mixes and energy bars to help you decide which is best for you

- Will you be entirely self-sufficient, rely on aid stations, or a mixture of both?

Whether you’re planning to be totally self-sufficient or rely heavily on the aid stations provided (or a bit of both), you’ll want to know what fuel sources and drinks will be available on course and when, just in case your plans have to change mid-race.

Elite marathoners usually have the luxury of picking up their personal bottles roughly every 5km (~3.1 miles), making it easier to meet their fueling and hydration needs without carrying anything from the start. To facilitate running at such high speeds, elite runners typically require a greater amount of carbohydrate and fluid to sustain their elevated outputs and energy use.

Here are some examples of the fuel you'd need to hit your carb numbers based on your target marathon time:

For non-elite runners relying on standard aid stations, a lack of preparation can lead to missed opportunities to fuel and hydrate effectively.

7 ways to optimise your aid station approach:

- Know exactly what’s available at each station, including how many grams of carb are in the gels, and whether there will be electrolyte drinks or plain water at each

- Know how often you’ll pass the stations based on your target pace

- Aim for the second half of the aid station tables to avoid congestion

- Make eye contact with the volunteer cup holder and even point towards them to make sure they know you’re aiming for them

- Slow down a bit if you need to, a few seconds here could save you minutes later

- Be present and aware - everyone is aiming for the same thing so watch out for other runners making sudden movements ahead of you

- Consider starting the marathon with a Soft Flask containing fluid and electrolytes. Being self-sufficient reduces risk and means you can avoid the early congestion of the first few aid stations.

Generally, if you’re not an elite marathon runner with access to your own bottles at aid stations, we’d recommend carrying a decent proportion of your race nutrition in a running belt, sleeves or pockets, so you’re confident of hitting your numbers.

Be prepared to adapt

"Everyone has a plan, until they get punched in the face."

One of Mike Tyson’s most famous quotes which applies to marathon running as much as boxing. Even with a dialled fuel and hydration strategy, things can go wrong mid-race. The key to success is to have a plan but be adaptable and flexible enough to be able to troubleshoot issues in real time.

GI discomfort is one of the leading causes of DNFs in endurance events. In running, the prevalence of stomach pain is even higher due to the repetitive ‘bouncing’ with each stride you take.

Staying clear-headed and focusing on what you can do is essential. Slow down, troubleshoot, and see if trying something different to what you’ve done up until that point.

Here are some common mid-race nutrition issues and possible fixes:

| Issue | Likely Cause | Possible Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea/bloating | Too much fluid or carb / Drinking or eating too fast | Slow intake, sip smaller amounts |

| Sloshing stomach | Overdrinking or poor fluid absorption | Reduce intake, add electrolytes |

| Cramps | Electrolyte imbalance or dehydration | Increase fluid & sodium intake |

| Energy crash (“bonking”) | Underfueling or starting fueling too late | Take quick-absorbing carbs ASAP |

Adapt to the weather

Most marathons take place in temperate conditions, but you’ll need to be prepared to adapt your strategy in the event of colder or hotter conditions…

- Cold conditions = Lower Sweat Rate = Less fluid needed

- Hot conditions = Higher Sweat Rate = More fluid needed

To give you an idea of a couple of the more extreme fluid intakes that we’ve seen, Malcolm Hicks drank ~1.1L (37oz) per hour during the extremely hot and humid 2020 Tokyo Olympic marathon.

Conversely, we’ve seen athletes drink as little as ~100ml (3oz) per hour in very cold conditions with no adverse effects from dehydration, so drinking relative to your individual losses is important when conditions dictate.

We generally recommend ‘decoupling’ your fuel from your hydration, so you can manage your carb and fluid intake separately. This involves relying on your bottles and flasks, as well as cups from aid stations, for your fluid needs. And use ‘solid’ fuel sources like gels and chews for your carb intake. This allows for better control of ‘The Three Levers’ in varying conditions.

For example, your fluid intake will inevitably be lower in cooler conditions, but you still need to be consuming carbs. So, using gels, chews or real foods instead of carb drinks to pull the carb lever is a good idea. .

In contrast, you’ll need to drink more to replace your higher sweat losses in hotter conditions, so using electrolyte-rich drinks will allow you to ‘pull’ on your fluid and sodium levers without over-consuming carbs.

How to start your marathon fueled

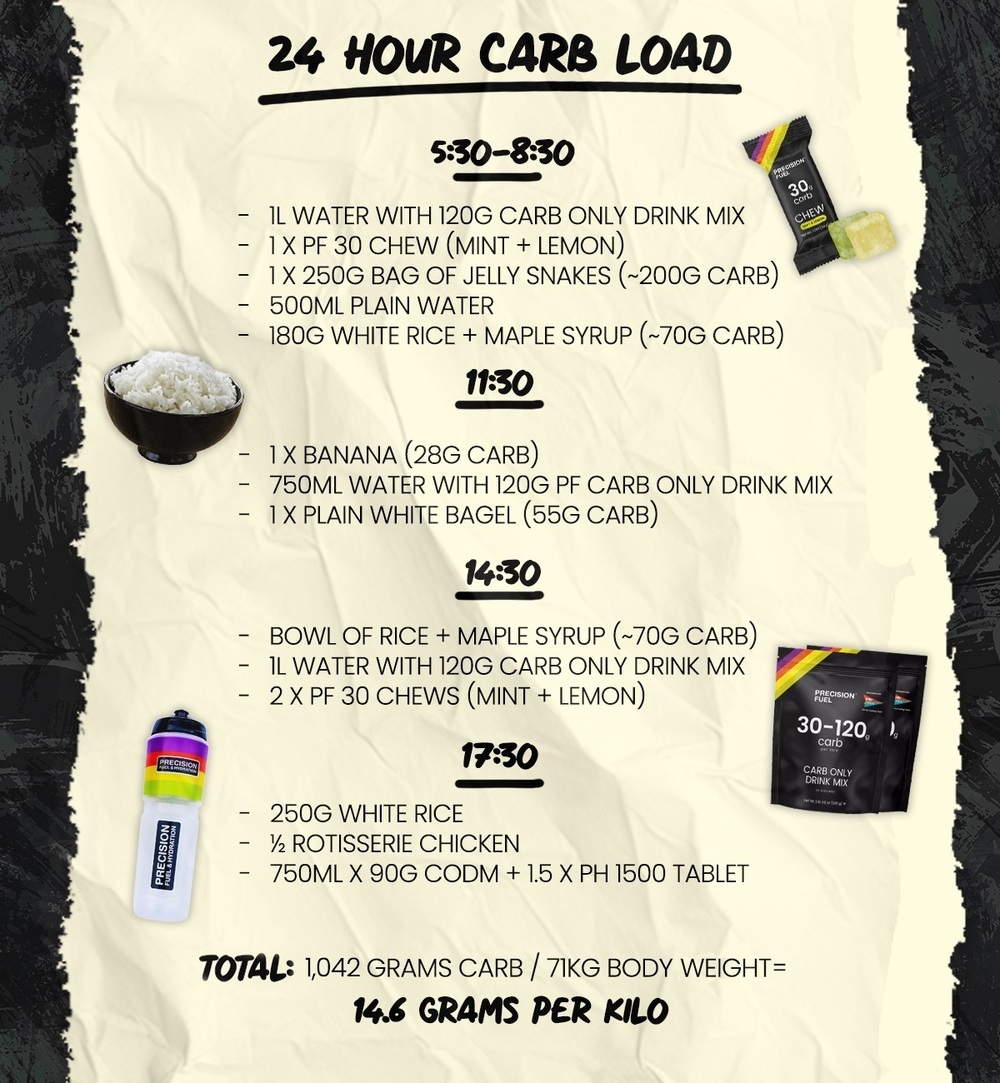

Contrary to popular belief, carb loading doesn’t simply involve eating a big bowl of pasta the night before your marathon.

The goal is to increase the proportion of carbohydrates in your diet while slightly reducing fat and fibre to avoid digestive issues during the 48 hours before your marathon.

How to carb load

- Target 8-12g of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight per day, for 1-2 days before the race. A 70kg (154lb) runner needs ~560-840g of carb per day

- Practice. Don’t try this aggressive carb-load for the first time before your biggest race of the year. Simulate a couple of times before key long runs and learn what types of foods and drinks you prefer, then replicate it ahead of your marathon

- Eat easy-to-digest carb sources like white rice, pasta, white bread, potatoes (without skins), bananas, carb drinks, sweets

- Avoid eating too much fibre which can cause bloating or gut discomfort (e.g. brown rice, whole wheat bread, lots of fruit and vegetables) and high fat foods (e.g. dairy or fried food)

- Consider using energy drinks like PF Carb Only Drink Mix to get additional carbs in, without increasing the size of your meals

- Each gram of glycogen is stored with ~3g of water, which can cause a small amount of weight gain in response to glycogen supercompensation. Don’t panic if this happens to you, it’s a normal response and a good sign you’re well stocked with energy!

Here’s a real-world example of my carb loading menu from my last marathon:

How to fuel on race morning

Your final carb-rich meal before your marathon should be seen as a ‘top-up’ of your liver glycogen stores, which drop overnight but are incredibly important during a marathon.

- Aim for between 1-4g of carbs per kilogram of your body mass, between 1-4 hours before the race starts (i.e. ~1g/kg one hour before, and ~2g/kg two hours out etc)

Finally, you can top up your circulating energy levels (glucose in the blood) with a 30g carb ‘hit’ 10-20 minutes pre-race. Because your circulating levels of adrenaline will likely be high, you’ll be breaking down glycogen in the liver at higher rates than normal, even before the race starts.

- Eat a gel or chew in the final 20 minutes before the race. This will provide you with additional glucose into the blood and can ‘spare’ some of your glycogen stores for later in the race, when you’ll really need it

How to start your marathon hydrated

When most people talk about hydration, the focus is on what and how much to consume during the marathon. Both are valid considerations, but your marathon performance will also be largely influenced by your hydration status before you start running.

A 2016 study found that despite the relatively obvious benefits of starting exercise well hydrated, more than 30% of 400 athletes were arriving at training sessions or competitions dehydrated.

This doesn’t mean you should drink gallons of water before your marathon. Unlike camels, humans don’t have the ability to ‘store’ water in large amounts, so overdrinking plain water will cause you to pee frequently. Over time, these regular toilet visits can actually dehydrate you as you’re peeing out vital minerals and electrolytes.

Instead, aim to drink a strong sodium-based electrolyte drink the night before and on the morning of your marathon. We call this ‘preloading’ and it’s worth testing out the following protocol before your next big training session:

- Drink ~500ml (16oz) of a sodium-rich electrolyte drink like PH 1500 the night before

- Drink another ~500ml (16oz) of PH 1500 on race morning, aiming to finish it ~45-60 minutes before the start. This will allow your body to absorb what it can, and pee out any excess

In short, drinking water with a high relative sodium concentration can stimulate some acute water retention, boost your blood plasma volume, and expand the reservoir of fluid to draw from when you’re sweating.

Should you use caffeine?

Carbohydrates, fluid and sodium should be the focus of your race nutrition strategy for your marathon. And once you’ve got those levers dialled in, it’s worth considering whether you could benefit from using caffeine as this is one of very few substances that’s scientifically proven to enhance performance for most athletes.

Research suggests that it can enhance endurance performance by 4-7% on average, meaning a runner targeting 3:30 for a marathon could potentially slash 8-14 minutes off their time.

But, caffeine affects individuals differently. Some runners experience a significant boost in performance, while others may struggle with side-effects like jitteriness, increased heart rate, or digestive discomfort.

How much caffeine should you use?

If you do use caffeine, most marathon runners will benefit from taking a dose before the gun goes off. Aim to consume 3-6 mg of caffeine per kg of body weight (1.4-2.7 mg/lb) ~30-60 minutes before the race (caffeine takes ~45-60 minutes to be absorbed into your bloodstream).

For a 70kg (154lb) runner, this equates to ~210-420mg of caffeine, which could come from a coffee with breakfast, a pre-race Caffeine Gel and a caffeine tablet.

If you regularly consume caffeine, sticking to your usual morning routine is advisable, but if your last dose is more than four hours before the race, you may need a top-up closer to the start.

- For a sub-3 hour marathon The pre-race dose is often sufficient as caffeine has a half-life of ~4-5 hours. An additional 50-100mg of caffeine later in the race may provide a noticeable boost towards the finish

- For a 3-5 hour marathon Pre-caffeinating is still important, but it can be beneficial to space out your later caffeine intake, ensuring levels remain elevated throughout the race. This typically involves consuming 1-2 mg/kg (~50-150mg per dose) every 60-90 minutes, while keeping the total intake within the 3-6 mg/kg range

- For a 5+ hour marathon: Caffeine’s effects will naturally diminish over time. Taking an additional 50-100mg every 90-120 minutes can help sustain alertness and reduce fatigue in the later stages. This may cause you to exceed 6mg/kg, but anecdotal evidence points to most athletes being able to tolerate higher doses without issue in these longer events

| When? | < 3 Hour Marathon | 3-5 Hour Marathon | > 5 Hour Marathon |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~60 mins pre-race | 3-6mg/kg | 3-6mg/kg | 0-6mg/kg |

| During the race | 50-100mg | 3-6mg/kg | 3-6+mg/kg |

Summary

Your marathon fueling strategy isn’t just about what you do on race day. Preparing your race nutrition plan in advance can be the difference between a PB and “presenting a picture of shock” when you cross the finish line.

- Know your numbers: Understand how much carb, fluid and sodium you need to perform at your best

- Know how you’re going to hit your numbers: Work out which products you’re going to use to hit your numbers, and what you’ll pick up from aid stations

- Refine your plan in training: Use training runs to train your gut and refine your strategy

- Carb load strategically: The days leading up to the marathon are just as important as race day itself. Dial in the right amount of carbohydrates to maximise glycogen stores

- Nail your pre-race meal: What you eat before the race can set the tone for your performance. Choose foods that are easy to digest and provide lasting energy

- Start hydrated: Drink a strong electrolyte drink the night before and on the morning of your race

- Consider caffeine: When used wisely, caffeine can enhance endurance and focus, but it’s important to test your tolerance in training

If you need help dialling in your marathon fuelling plan, book a free one-to-one Video Consultation to discuss your strategy.