Tapering to reach a peak for a specific event is often described as both an art and a science.

Abby has covered the current scientific consensus on tapering and, while I certainly wouldn’t describe myself as an ‘artist’ of any sort, I’ve summarised a couple of very different tapering experiences I had when building up to my ‘A’ races in 2003 and 2005 in order to provide an anecdotal perspective on the subject.

The two tapers preceding these races were fundamentally different in many ways but both resulted in good performances, so it hopefully goes some way to demonstrating that, when it comes to what you do in the immediate build-up to an event, there is more than one way to cook an egg.

The key to any good taper (and indeed cooking an egg) is to make sure you’re not overcooked or raw…

2003: The ‘textbook’ taper

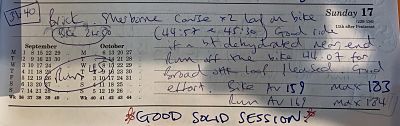

During the early months of ‘03, according to my meticulous (if somewhat scruffily) handwritten training diaries, I was regularly logging 15 to 20 hours of hard training per week and soaking it up nicely.

I was on a mission to get a spot for the IRONMAN World Championships at Kona and was targeting a 70.3 (or half-IRONMAN as it was known then) qualifying race in Sherborne, Dorset, in the build-up. I was on a decent upward trajectory month-to-month, clocking PBs in running races, cycling time trials and winning a number of build-up triathlons throughout the early season.

The qualification race was on 31st August and when I was exactly 2 weeks out, I did my last big session before starting my taper (the workout was just under 3 hours with long race pace efforts on the bike and a 45-minute hard run immediately after) - just as the science of tapering suggests to be optimal.

Satisfied that I had ‘done the work’, I then began to cut back on the volume whilst keeping elements of high intensity in to stay sharp and maintain my fitness whilst ‘freshening up’ at the same time - again just as the theory told me I should.

Two weeks out, I dropped the number of training hours down to about 11.5 hours and then to around 7 hours (not including the race) in the final week. This was a reduction of about 40% and 60% in total volume compared with my typical weeks in the build-up.

I kept some interval sessions in the plan, such as 6 x 800m running with 3 minute recoveries - the reps were well above goal race pace and I even did a little aquathlon swim/run race on the Wednesday immediately beforehand.

In most of my diary entries during the final week it says things like ‘felt fidgety and excited’ or ‘legs feeling lively’. On the day before, I did a 35-minute run on the actual race course and wrote ‘Felt great. Can’t wait!’.

Reading it now it seems all but inevitable that I was going to have an excellent race and that’s exactly what happened. ‘Best race ever!’ reads the note against Sunday 31st August in my diary.

I managed to come in 3rd overall and to beat most of the pros in the field, winning my age group by 17 minutes and punching my Kona ticket.

When I now reflect on tapering for this race, it was basically done almost exactly in agreement with what the science tells us is optimal. This was ‘easy’ to achieve because I had a relatively uninterrupted build-up, my confidence was high and I was able to commit to the process of reducing overall load whilst maintaining the frequency and intensity of training at the expense of volume.

I also managed to go into the race in a very relaxed state of mind - something that’s not always emphasised in the studies looking at how to taper - and I definitely feel like this was hugely positive in giving me the mental reserves to dig deep on race day and really go to ‘the well’ to draw out my best possible effort.

2005: an enforced early taper

In 2005, my A race for the year was IRONMAN UK. Held at the same venue where I’d had success in 2003 at the half-distance, I was determined to see what I could really do over the long course distance having underperformed in Kona in '04.

Unlike 2003, my build-up through 2005 was more up and down with a couple of niggling injuries and repeated periods of fatigue and mild illness reducing the consistency of training.

With the hindsight offered by going back over my diary for the first half of the year, it’s clear that I was constantly treading the line of overtraining and frequently getting on the wrong side of it.

The race was on 21st August and about 3 weeks prior when I should have been putting in some of my biggest preparatory workouts, I wrote in my diary ‘Day off, slept in. Feel tired and unmotivated, lethargic and p*ssed off. Oh dear.’

At this point I remember talking to Paul, my coach who advised me to simply back right off and rest up - only training very light and short sessions (i.e. reducing volume, frequency AND intensity - not what the tapering book says at all) in order to try to recover some motivation and energy before the race.

I did this as I basically felt I had no other option, doing little more than a single jog, spin on the bike or easy swim per day. My training diary entries for the next week look like the kind of thing Winnie the Pooh’s friend, Eeyore, would have written if he was trying to train to be a triathlete. It was all negativity, until on August 8th a little bit of positivity crept back in. I did a 45-minute run that day and wrote that I could feel ‘a little liveliness coming back’.

I ticked over for a few days more and then completely out of the blue on August 13th - just 9 days out from the race - Paul asked me to do a 2.8 mile time trial run as fast as I could.

Despite the fact I still didn’t feel quite right in myself, Paul said he was convinced that I was now physically pretty well recovered from whatever was ailing me before but mentally fragile about my lack of form, and he wanted to prove this to me. He felt that a good run over his little ‘test route’ where he had times of some top runners over the years would get me back on track for the final week so I could go into the race with confidence.

He didn’t allow me to wear a watch or heart rate monitor for the test (I did for nearly all sessions back then) but instead drove his car to time the run and get some splits.

I remember setting off hard but not quite at maximum and then proceeded to bury myself after half way to see what kind of time I could do. I ran 13 minutes 20 seconds for the route (~4 min 45 per mile / ~2:55 per kilometer) on a rolling, twisty route with a dead turn at one end and recall being totally surprised by my form.

It was one of the quickest times Paul had seen on the route and was a solid indication that I was not totally fried as I’d feared.

In the final week I continued to merely ‘tick over’ with the training, doing less than an hour a day at a low intensity because Paul and I decided that this was the safest thing to do with a ~9 hour effort coming at the weekend.

Come race day, I was still nervous and less confident than I had been going into 2003 but the time trial ‘result’ gave me some belief that I could still do well. My result (9th overall, 3rd Brit) was very solid and in line with what I could reasonably have expected given the depth of the field and my experience at the distance.

What I learned about tapering from this particular experience was that sometimes you have to be prepared to throw out the textbook entirely and make it up as you go along if your preparation has been less than perfect.

Specifically, I learned that if you’ve ‘done the work’ in the sense that you are sat on a number of months of training but are feeling excessively fatigued, demotivated or overdone, then it can be necessary to de-load things almost completely in order to prioritise recovery over optimisation of fitness gains.

I also gained an appreciation for the importance of having a good mentor to guide you through a tricky taper.

The external perspective Paul was able to bring by making me do a tough time-trial right at the point I had almost totally lost confidence in my ability and form was something I would never have done off my own back. This was the most significant factor in salvaging a decent performance from a situation that was otherwise looking like a bit of a train wreck.

Does a 'perfect taper' exist?

I think the key thing to remember with any taper into a race is not to get too caught up in it needing to be entirely perfect for it to allow you to deliver a good performance at the end. No matter what the science suggests is optimal.

If things do go swimmingly, as they did for me in ‘03, then that’s brilliant. But this is quite rare.

If in doubt, my general advice based on many other less than optimal tapering experiences is to be cautious and rest up a bit more than you might think necessary. Ultimately, physical and mental freshness can allow you to really step up on a given day.

On the other hand, taking lingering fatigue into an event has never really helped anyone when it comes to digging deep and so avoiding this at all costs should take precedence in most situations.