Taper (verb): to diminish towards the end

In a sports setting, a taper refers to a phase of reduced training load that you might undertake in the lead up to an important competition.

The purpose of this taper is to optimise competition performance by reducing the negative impact of daily training (i.e. accumulated fatigue) without suffering a loss of the training adaptations (i.e. detraining) you’ve spent many weeks or months gaining.

With well-planned training, by the time you start tapering you should have achieved all or most of the expected physiological adaptations so, as soon as the accumulated fatigue diminishes, your peak physiological and psychological performance can rise to the forefront...

How to design your optimal pre-race taper

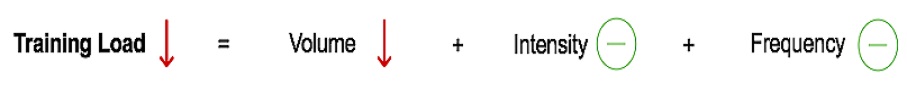

Tapering broadly means reducing an athlete’s ‘training load’ - described as a combination of the training volume, intensity and frequency.

Tapering effectively comes down to striking the right balance between these three factors, as well as nailing the duration of the taper.

It’s worth remembering that tapering might not be necessary ahead of each and every competition or race scenario. That said, it is a good idea to experiment with a reduction in training load, be that a formal tapering period or not, ahead of your key ‘A’ races.

Certainly, the more over-fatigued and overstretched an athlete is at the point of concluding their final mesocycle of training, the more effective, and necessary, the tapering period will be.

Training volume

An athlete’s training load should predominantly be reduced by decreasing total training volume - i.e. the amount of work done (e.g. number of reps and/or miles run).

Research has shown that a 40-70% reduction in training volume compared to the pre-taper training cycle is the optimal decrease.

That said, your sport might influence your taper. For example, some evidence suggests runners might benefit from a reduction as big as 80-90% in training volume. This is because of the greater demand running places on the body when compared to low-impact activities like swimming and cycling.

For multi-sport athletes, like triathletes, reducing their running volume can easily be compensated for by maintaining some or all of the volume in their swim and cycle sessions.

Training intensity

It’s easy to think the intensity, like training volume, should be reduced when tapering but this isn’t the case.

It has been repeatedly demonstrated that upholding training intensity and maintaining some ‘quality’ sessions is an essential requirement for keeping hold of those training-induced adaptations during periods of overall reduced training load.

For instance, a study compared a high-intensity low-volume taper with a low-intensity moderate-volume taper in middle distance runners. They found the retention of training-induced adaptations was optimised only in the high-intensity taper.

Training frequency

Unlike the intensity, you can afford to be a little more lenient with the frequency of your training during a tapering period. It has been found that within “moderately trained” individuals, training adaptations can be maintained with relatively low training frequencies (between 30–50% of pre-taper values).

That said, higher training frequencies (>80%) are encouraged for “highly trained” athletes, especially in more “technique-dependent” sports, such as swimming. This helps to keep the ‘feel’ for the sport and maintain key movement patterns.

The general consensus is that if you can (and want to) maintain a high training frequency in the lead-up to competition, this is unlikely to hinder your race-day performance, as long as the volume of these sessions is reduced accordingly.

Taper duration

The fourth and final factor to consider when designing your taper is the duration. The literature has tested a wide range of taper lengths, from as little as 2-3 days up to several weeks, and the conclusion is that between 10 to 14 days is appropriate for most individuals.

That said, some athletes might benefit from reducing their training load prior to competition earlier than this, as much as three to four weeks, depending on how overreached or fatigued they feel both physically and psychologically.

In contrast, others (or even the same athlete in a different situation) might maintain their training load closer to race day, choosing to taper for a week or less. Both have been shown to be effective when applied correctly.

Those who adapt, and importantly lose, training-induced adaptations quickly might be better off with a shorter taper duration.

Those who are slower at adapting but seem to hang onto these adaptations for longer, might find a steadier, more gradual decrease in training load more appropriate.

Science may well earmark this as the key factor to determining taper length, but it’s often not this simple in practice. Andy highlights this issue in his blog where he dissects and outlines two successful but very different tapers he underwent during his triathlon career.

Different models of tapering

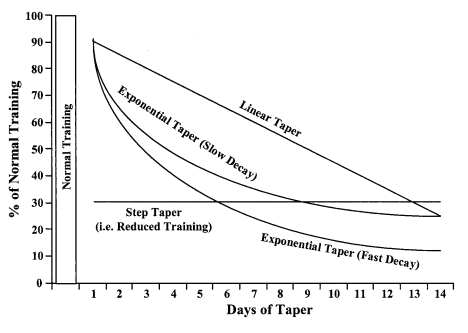

In his review paper published in 2003, Iñigo Mujika, a sports physiologist and associate professor at the University of Basque Country, outlined four different taper profiles and used the graph below to illustrate the differences (something he also discusses on the ‘That Triathlon Show’ podcast).

Broadly, how a person tapers can be divided into two overarching themes:

- A single reduction in training

- A progressive reduction in training

A single reduction in training

Step taper

A step taper involves reducing training volume by a given percentage and maintaining this until competition day (see the straight line on the graph above).

In this instance, the athlete has reduced their training load to 30 percent of their normal load. It’s a one-step, single decrease which is viewed as less effective than progressive-type tapers.

A progressive reduction in training

Exponential tapers

An exponential taper can have a fast or slow decay. This relates to the rate at which the progressive reduction in training load occurs. A fast decay taper reduces training load more substantially and is largely considered the most effective tapering method.

In either case, the initial reduction in training load is greater at the beginning of the taper and stabilises at around 40-60% of the prior load as an athlete gets closer to competition day.

Linear taper

A linear taper involves reducing the training load in a straight-line fashion.

As a simple example, a runner covering on average 10km a day in their previous training cycle might reduce their training volume by running 1km less each day.

Note in the graph above that a linear taper usually implies a higher training load than an exponential taper (the area under the curve), which may explain why it produces less pronounced positive outcomes on performance when compared to exponential tapers.

In practice, it isn’t feasible to stick to such rigid or exact percentage decreases, and you don’t have to decrease your training volume every single day. All of the models described should be viewed as ‘concepts’ to outline the design of a taper, open to interpretation depending on an athlete, and a good taper will require some flexibility.

Choosing the right taper

Regardless of the science and the general consensus around tapering, a taper should be individualised.

Some athletes will feel like they need a longer taper than others, some may require more volume, some might have a preference for a lower frequency. This kind of insight is gained from experience of building up to races over time and also knowledge of how your body responds and adapts to different stimuli. It’s a process that might take some time to refine and should be evaluated regularly.

Other considerations when tapering

Lastly, when tapering, the more focus you can put on recovery, the better. The two most important recovery methods to pay attention to are nutrition and sleep, and you can read more about those topics here, here and here.

Key tapering takeaways

- A taper is not an excuse to put your feet up. Whatever decrease in training load you opt for, the training you do should still be viewed as important and impactful on your race-day performance.

- Athletes should bear in mind that an insufficient training stimulus could bring about a partial detraining effect and/or a “loss of feel” (particularly in highly trained individuals). Therefore, aiming to maintain a high level of training frequency and intensity is important.

- The main reduction in training load comes from doing less total volume of work - fewer reps, less miles!

- The right balance needs to be struck and it may take some time to get a taper right – keep evaluating the taper period.

- Tapering isn’t always necessary. It’s something worth experimenting with, especially before big ‘A’ races, but it might not be a requirement before every single competitive scenario.

- Keep in mind that sometimes you need to step away from the rule book and really listen to how you’re feeling pre-competition. A taper should be individualised and you shouldn’t be afraid to switch up the tapering period if it feels necessary.