The topic of body types in elite sport has always lead to interesting, and often controversial, observations.

Basketball players are typically stereotyped as tall and lean, whereas weightlifters are generally categorised as being short and wide. A low centre-of-gravity (aka short) seems advantageous for gymnastics but won’t get you far on a volleyball court, whereas thinness is as synonymous with ballet as obesity seems to be with sumo wrestling.

Where things get more interesting though is when there’s less of a clearly defined ‘perfect body type’ for a sport. For example, what is the most advantageous body for an IRONMAN triathlon which combines the attributes of three different sports? After all, a freestyle swimmer would typically be defined as ‘top heavy’ with broad shoulders, whereas cyclists are traditionally ‘bottom heavy’ with strong quads, while a distance runner wouldn’t be expected to possess either trait.

It’s little wonder that we usually see a mixture of different body shapes and sizes on the start line of IRONMAN races. The general assumption has always been that smaller and leaner is better for swim-bike-run athletes, but is this necessarily the case?

Does the perfect body for triathlon exist?

I was flabbergasted by some of the comments that followed Kristian Blummenfelt’s dominant victory in May’s IRONMAN World Championship in St George, Utah. People seemed more fixated on the idea he looked less like a triathlete and more like ‘a rugby player’ than the fact he had just beaten the very best endurance athletes in the world by a healthy margin. Even his fellow competitors, the very people who had just been dealt a lesson on how to perform on the biggest stage, were eager to pass comment on his body shape after the event.

At first, I was surprised by the comments but I quickly became frustrated and even angry at the fact we were unwilling to dedicate the title of ‘best body type for IRONMAN’ to the one we’d just watched defeat the very best athletes in the world. The fact is, Blummenfelt might well have the perfect physique to make a career as a rugby fly-half, but we now know with absolute certainty that he has a body for triathlon. After all, Kristian has the Olympic, middle and long distance titles to prove it.

Typically, those of us who choose endurance sports also have an interest in body image. Often our way into the sport has been driven in some part by a desire to look and feel good. The line becomes blurry though when we begin to perceive food less as fuel and more as a compromise on our pursuit of a ‘perfect’ body.

When it comes to training for high volume sports like triathlon, cycling, rowing or swimming, we see huge amounts of energy expenditure, regardless of whether you’re competing at a recreational or elite level.

Focus on fueling and training

Fueling for performance usually requires much larger amounts of food intake than those of the general population and even athletes who compete in sports that require less overall training volume (such as speed and power sports). The key to success in these high volume sports is the ability to train consistently across weeks, months and seasons. Usually the greatest threat to our ability to train consistently is injury and illness, and we develop a much higher risk of both if we’re fueling inadequately.

Injuries in triathlon will very often have something to do with structural faults in bone, muscle, tendon and ligament tissues. Illness is more likely when our immune system is suppressed. The biggest step we can take towards minimising injuries and illness sits with our ability to achieve adequate energy intake and meet all macro and micronutrient needs. In other words, we need to eat plenty.

In my experience, the main reason we don't fuel adequately for endurance performance is our fixation on body composition and the belief that eating less will make us leaner and subsequently better at our sport.

What Blummenfelt’s stunning victory in St George reminds us is that performance is the product of fueling well and training consistently. If we do these two things, our body composition will run its course. Genetics will play their part too, as they do with everything. If Blummenfelt had different parents he might have ended up with a totally different physique, but his VO₂ max and lean body mass might also have been lower and he possibly wouldn’t be an Olympic and World Champion right now.

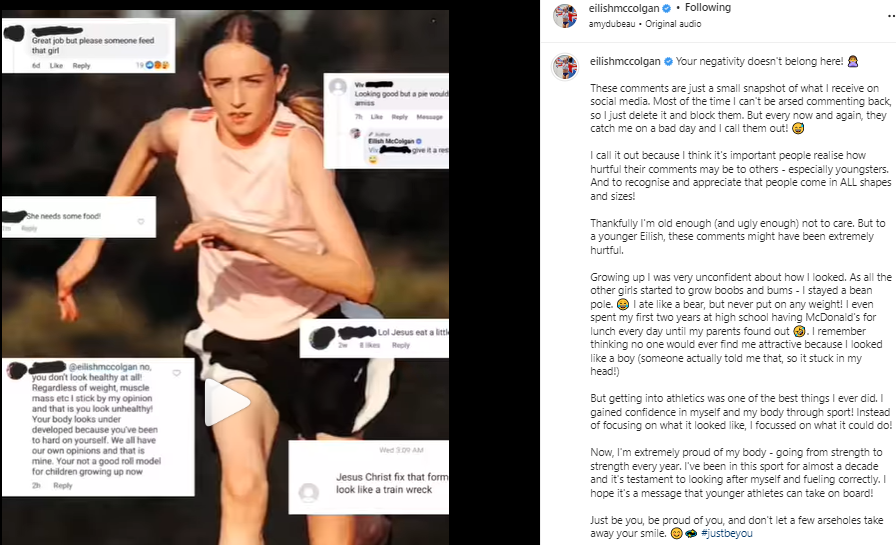

Unfortunately, the unnecessary focus on the supposedly 'perfect' body shape for a specific sport isn't only limited to Kristian Blummenfelt and triathlon. My fellow PF&H athlete and 3x Olympian Eilish McColgan has shared her own negative experiences of people commenting on her body shape rather than her record-breaking running performances.

Maximise your body

Conversations with athletes who I coach around body composition are never easy. My view is that we must see body composition as a by-product of fueling and training well. Not vice versa. That is: rather than viewing our ability to restrict calories and reduce body weight as being beneficial to performance, we need to see our ability to eat plenty and train consistently as being conducive to achieving healthy and optimal body composition markers. The former is more likely to lead to injury, illness and disappointing performances, whereas the latter is likely to lead to success in sport and overall health (even if we find ourselves a few kilos heavier; likely due in large part to muscle growth).

Of course, as training volume is compromised by work, family and life, we need to be mindful of what constitutes ‘adequate fueling’. But energy, health and injury status are more often the things that restrict our ability to train consistently than time availability. So once again, our ability to see food as fuel for performance, recovery and health is the best mindset we can use to help frame body composition.

I’m certainly not claiming it's going to be as easy as ‘deciding to eat well, train smart and accept your body for what it is’. As an elite athlete who has always sat around ~83kg, I've grappled with different lenses through which to view my body. I always feel self-conscious on a start line as I look to both sides and see much smaller athletes surrounding me. But with time I have come to appreciate the many important qualities that my larger (relative to many of my competitors that is) frame has on offer.

‘Power to weight’ is a reference to BOTH power and weight. Power is produced by strong muscles. Resilience to the big training miles has a lot to do with a strong skeleton (which also weighs more than a soft and brittle skeleton). Regular aerobic exercise helps grow a bigger heart and set of lungs (and once again, these weigh more than small organs that can’t deliver as much oxygen to working muscles, aka VO₂max). You get the idea I’m sure: ‘weight’ always needs to be viewed in context.

In the end, my belief is that our goal should be to maximise how ‘functional’ our body is, regardless of shape, size and mass. As the saying goes: no matter how slow you’re going, you’re still lapping everyone on the couch. An injury or an illness usually leaves us sitting on the sidelines.

So, let’s continue to aim to train consistently, fuel for performance and be accepting of the size and shape our body morphs towards as a result. Sitting on the couch is never as fun as being out there pursuing our endurance goals, while living an active and fulfilling lifestyle.

We won’t all be winning Olympic and World Championships like Blummenfelt, but we can all be inspired by the way he has shown ‘the perfect body for triathlon’ is really just one that is healthy, injury-free, conditioned and well-fueled.